The Indio mall is a surreal place.

Step through the doors most days and you’ll find the noise of outside traffic replaced with a jarring silence. A few shops sit wedged between mostly shuttered storefronts, some serving a trickle of customers, others perennially empty.

The central fountain usually hosts one or two seemingly lost souls licking ice cream or staring off into space to the sounds of gurgling mall water. The filtered lighting makes it hard to tell what time of day it is or how long you’ve been there.

Decades of scandal and broader economic headwinds have driven this mall into a slow decay, leaving it largely empty and limping along in a zombie-like half life. The 1990s saw all residents in one of the Coachella Valley’s few Black communities — located immediately behind the mall — evicted and their homes razed to the ground to make way for a mall expansion that never happened. That land is now a largely barren expanse of dirt and weeds.

New owners with grandiose plans came and went, generally leaving the mall worse than they’d found it. It spent the better part of the past decade as a collateral casualty of what the SEC called a massive “Ponzi-like” scheme.

The mall, known for most of its history as the Indio Fashion Mall but now branded as the Indio Grand Marketplace, was once a centerpiece of the Coachella Valley’s largest city. It’s Indio’s first and only enclosed shopping mall and, at one time, was a major employer, community gathering place and financial engine for the city. A 1978 Desert Sun headline proclaimed that the mall “changed (the) city.”

Now, the owners of the Empire Polo Club — home to the world-renowned Coachella and Stagecoach music festivals — want to return the Indio mall to its former glory. After several years of delays, the Haagen Company plans to break ground on new construction this summer and turn “an old eyesore” into “an asset for the city.” They aim to transform the land that was once the Nobles Ranch community into an apartment, hotel and restaurant complex with a public park, complete with a tribute to its displaced residents.

Whether the new owners can break the curse that seems to loom over this ill-fated mall remains to be seen. While experts say these types of revitalization projects have a mixed track record, city officials say the new owners’ ties and commitment to the Coachella Valley makes them confident this time will end in success.

Dismembering a community

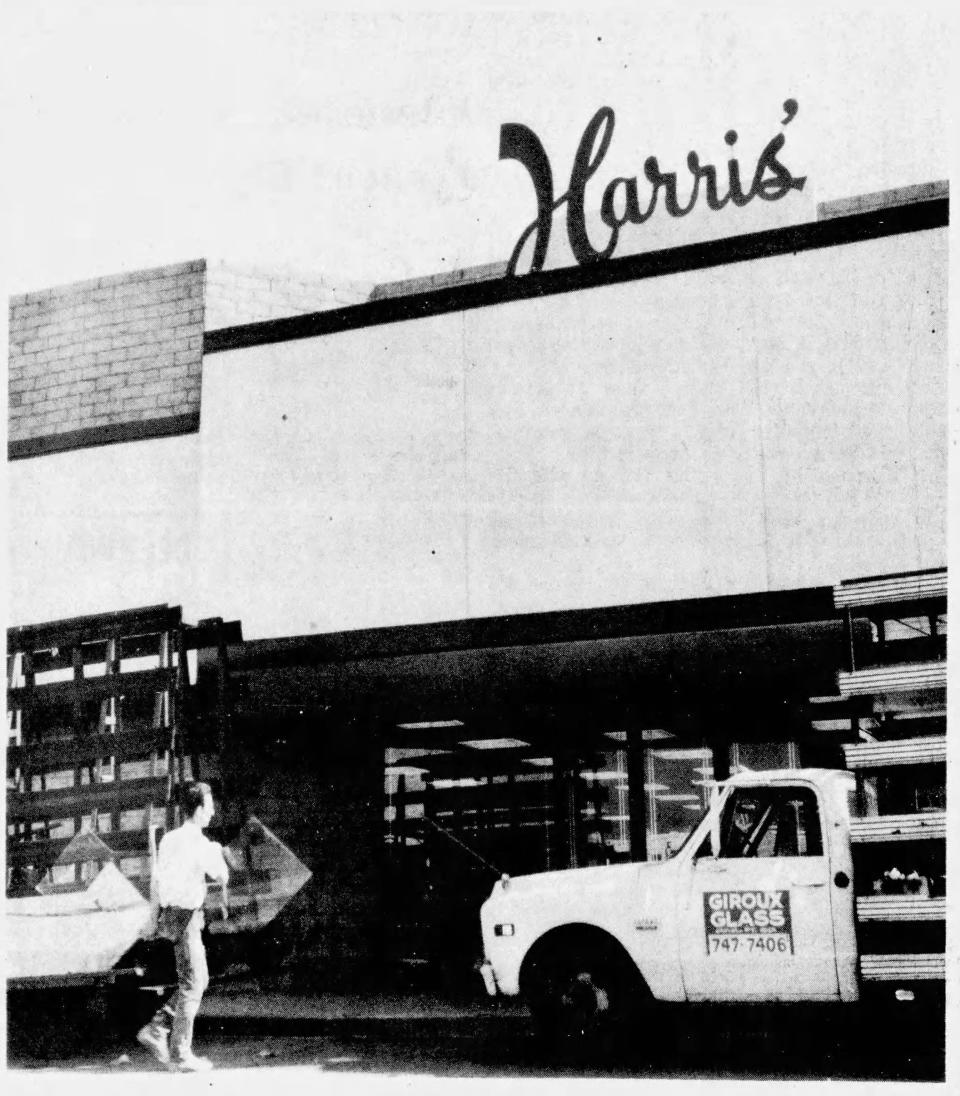

The Indio mall opened with a bang in 1975. The ribbon-cutting ceremonies saw the Indio High School Band play alongside a speech by the president and general manager of the Harris’ Company, a now-defunct department store chain that joined Sears as the largest stores at the mall.

The exterior was emblazoned with the eclectic façade the mall would bear for the next four decades — an art deco-esque “Indio Fashion Mall” sign overlaid on palm fronds below a stained glass panel with the same words written into it. A contemporary Desert Sun article described the upper façade as a “Byzantine motif.”

By most accounts, these early years were good ones for the Indio mall. Current Indio Mayor Waymond Fermon, who grew up a few blocks from the mall, called it a “centerpiece for our city” in its early years.

“It was a place where our kids congregated, our adults shopped and it was a place where — on the weekends — families gathered for a day out,” Fermon said. At the time, the mall had the Sears and Harris Company stores, a Miller’s Outpost clothing store and a host of small shops such as a Zale’s Jewelers, Valley Hallmark Cards and Books, Desert Beauty World and Jeff Lilley’s State Farm Insurance.

A 1978 Desert Sun article made the claim that the mall drew shoppers from not only the eastern Coachella Valley, but also “from Palm Desert, Rancho Mirage, Cathedral City, Palm Springs and the high desert cities of Twentynine Palms and Yucca Valley.”

The good times wouldn’t last, however. Just over a decade after the mall’s completion, one of its — and the city’s — darkest chapters began.

In the mid-1980s, an agent of then-Indio Fashion mall owner David Miller approached the city with an enticing proposition. The plan, according to contemporary Desert Sun coverage, was to double the size of the mall, adding 100 new stores and all the accompanying tax revenue and jobs.

The catch? The project would require the city to raze an entire neighborhood with more than 80 homes, three churches and a housing project and relocate hundreds of residents — by force if necessary.

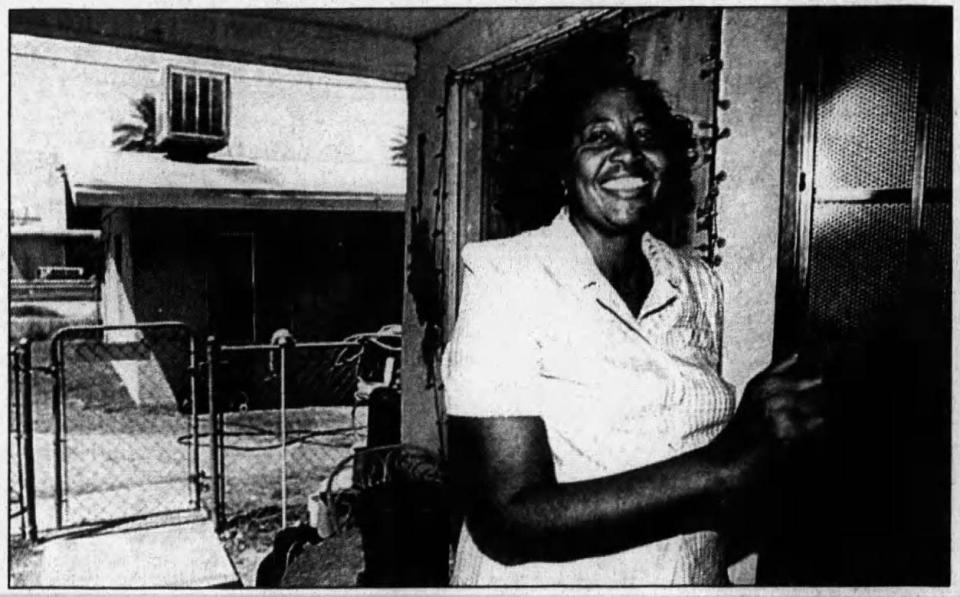

The Nobles Ranch community immediately behind the Indio mall was one of the city’s only majority-Black neighborhoods. It was founded by the eponymous John Nobles, a Black sharecropper — likely from Oklahoma — who came to the Coachella Valley in the 1930s.

Many details of Nobles’ life have been lost to history, but the stories of residents and others with connections to the sharecropper generally follow a few broad strokes.

Nobles acquired the property that would become Nobles Ranch at a time when discriminatory practices made it difficult or impossible for Black people to acquire land in many areas, including in the Coachella Valley. He then gradually sold off or gave pieces of his land to incoming Black settlers and workers, laying the foundations for the formation of one of the area’s first and few Black communities.

More than 50 years later, a deal was struck between Miller and city officials to level that community and replace it with a bigger, better Indio mall. After negotiations broke down between the city and some residents, officials decided to take the land via eminent domain — the government power to take private property, usually for public use. The resulting mess was a standoff that saw everyone get hurt.

Some Nobles Ranch residents enlisted the help of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to sue the city and stop the development. That suit scared away Miller’s investors, prompting delays and, eventually, driving the mall owner to pull out of his deal with the city. The ensuing litigation between the city and Miller dragged on for years before resulting in a roughly $10 million settlement that was almost enough to cover the costs the city had spent on the land and wipe away its debt.

It didn’t save the neighborhood, however, which was mostly demolished throughout the 1990s, with residents scattered across the Coachella Valley and out of the area. A 1998 Desert Sun article cited residents who signed onto the NAACP lawsuit saying they got better deals for their replacement homes than those who had simply fallen in line with city orders. Former Indio Community Development Director William Northrup countered that most residents got moved into homes worth more than the ones they had left, regardless of whether or not they participated in the lawsuit.

Pastor Carl McPeters of the Kyriakos Christian Center, one of three predominantly Black churches in the neighborhood, recalled his experience trying to hold services on a Sunday morning when the city showed up to destroy a nearby residential building via a controlled burn.

“Of all the days they could have done that; they did it on a Sunday morning,” McPeters said. He said the smoke filled the neighborhood and conjured up images of burning crosses in the American South.

“Still when I think about it, it was hard to believe a progressive city (in the year) 2000 —,” McPeters said, trailing off before continuing. “We should have gotten past all of that.”

Indio city officials declined to comment on that specific incident, saying the issue predated current staff and they were unaware of the details.

“It was a tragedy,” said current Mayor Fermon of the Nobles Ranch evictions. Fermon, who became Indio’s first Black mayor in December, said he had relatives who lived in Nobles Ranch and were displaced when it was destroyed.

“It was just a dark moment in our history,” Fermon said. “It really dismembered the African American community in our city.”

The mayor said he is unable to rewrite history, but is focused on trying to improve conditions for Indio’s remaining historically Black (but now mixed-Hispanic) communities. He said he was optimistic that a successful revitalization of the Indio mall and accompanying development of the former Nobles Ranch land could provide “services, resources and economic opportunities for generations to come.”

Today, one old wooden church — McPeters’ still-active Kyriakos Christian Center — is all that is left of the Nobles Ranch community. It stands like a mirage amid acres of barren desert dirt.

Nothing was ever built on the Nobles Ranch land. It has lain fallow for nearly 30 years while the mall that marked its demise has slowly declined.

Fraud and decay

After several fits and starts, Miller — who had retained ownership of the Indio mall following the collapse of the Nobles Ranch expansion plans — managed to find a buyer to take the property off his company’s hands in 2003. Although the mall was already stagnating, he reportedly managed to convince Malibu-based developer Richard Weintraub to pay $16 million for the property.

Weintraub’s ambitious plans involved turning the mall — and the former Nobles Ranch land — into a “lifestyle center” complete with restaurants, entertainment, residential space and retail. He technically changed the name to the Indio “Fiesta Mall,” which never stuck, possibly since the old façade remained loudly proclaiming the Fashion Mall name.

Instead of a revitalization, the mall received two grievous blows when its largest stores, known as anchor tenants in retail jargon, closed down. Sears packed up and headed for Palm Desert in 2004, while Gottschalks — which had replaced the Harris’ store in 1997 — was liquidated amid a bankruptcy in 2009. Those departures, coupled with the onset of the Great Recession, devastated the mall.

Real estate experts say the sudden loss of anchor tenants is a common thread running through the stories of many dead or zombie malls — the latter clinging to a type of half-life for years after most tenants have left.

“The general belief among us real estate investors is that anchor tenants drive traffic to the mall,” said Joseph Pagliari, a professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business who studies commercial real estate investments. “Because these department stores would sell multiple lines of merchandise, they’d have a broad cross-section of customers and then that customer might come to the mall, shop at the department store and then hit one or more of these (smaller) stores.”

Pagliari said the closure of anchor tenants — aided by and coinciding with the rise in online shopping — kicked off a process of slow economic rot at many malls, as store closures led to fewer customers, which led to more store closures.

The Desert Fashion Plaza, built in downtown Palm Springs and opened in 1967, struggled with high vacancies and low customer traffic for decades as it decayed into a zombie mall. The city eventually helped pay to have it torn down and redeveloped into the Kimpton Rowan Hotel, shops and restaurants — but not before multiple legal battles and an ongoing corruption probe involving the project’s developer and the former mayor.

Meanwhile, The former Palm Springs Mall sat as a largely vacant eyesore for years before the College of the Desert announced its intention to buy the property and use it for a new west valley campus. It took another five years of negotiations and a lawsuit before the college acquired and demolished the mall in 2019 — although what it will build there and when remains unclear.

Pagliari said cities were often reluctant to give up on malls even after this process of economic rot had clearly set in — motivated, in some cases, by a combination of taxes and zoning.

“In most jurisdictions, the retail sales tax generated by these malls can be a huge part of the local government’s budget,” Pagliari said. “And so local governments are oftentimes very prone to trying to figure out ways to help or sustain (them).”

He noted this tax incentive might also at least partially explain a city’s willingness to use eminent domain in a bid to save or improve a mall, a situation he said was not entirely unique.

He said the difficulty in shifting the use of a former mall property — especially one located near residential areas — can also often prevent a mall from fully dying even after its economic viability is gone.

“In other words, some of these municipalities are still clinging on to the hope that a better retail day will happen in the future,” he said.

In 2009, Weintraub’s company made some exterior repairs to the Indi mall, such as a new paint job, reflecting what a marketing representative told The Desert Sun at the time was “the real commitment the mall’s owners have to Indio’s business community.” He sold the property for $8.5 million just over a year later, according to property records, to a company called REO Property Group.

That decision would kick off one of the most tangled chapters in the mall’s history.

It began quietly. Years passed with little public information from the new owners on their intentions for the mall. Court documents would later reveal that REO Property Group, headed by Los Angeles-area couple Frank and Hilda Zeng, attempted unsuccessfully during this period to sell the mall for $12.8 million — despite the fact that it was 80% vacant. They had taken on $6.5 million in debt to fund the original purchase, according to property records.

Then came the most grandiose plans yet.

A representative for REO Property Group told the Desert Sun in 2014 that the company aimed to build a water park, hotel, auditorium and community park in a $150 million development that would, again, encompass both the mall and the former Nobles Ranch land.

It’s unclear where the balance of that mammoth project cost was to come from, but at least part of it was to be drawn from a group of well-heeled international investors through the EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program. That program essentially allows foreign investors to receive a Green Card in exchange for investments in the United States.

Court documents detail a Byzantine funding structure that would — in theory — channel millions of dollars from Chinese and Taiwanese investors into the mall revitalization project. These funds would come through investment entities managed or owned by a Pasadena-based individual named Yin Nan “Michael” Wang.

Under the arrangement, a new company, confusingly called REO Group Property, bought most of the mall in 2013 with funds from Wang’s investment vehicles. REO Property Group retained the southwest corner of the mall property — today home to a standalone structure with a meat market, Chinese restaurant and other small businesses. Investors, who later sued the Zengs, their company, Wang and others, allege in court documents that they were misled about the financial health of the mall, which their attorneys described as “essentially worthless.”

When reached for comment, Frank Zeng said his attorneys had advised him not to speak in light of ongoing litigation. He said a lawsuit later brought by investors against him, his wife, their companies and others, was “not about the mall,” but declined to answer further questions.

Attorneys for the investors declined to comment on the situation while litigation is ongoing.

Later that year, the Securities and Exchange Commission brought a civil action against Wang alleging that he and his partner Wendy Ko had lied to investors and used incoming funds from his various investment entities to pay off obligations to other entities in a “Ponzi-like” fraud.

All told, the SEC alleged that Wang had collected more than $150 million from 2,000 investors. In 2016, a court ordered Wang to pay disgorgements of more than $81 million for ill-gotten gains plus a $6.5 million pre-judgement interest fee and a civil penalty of $1.5 million. The investors allege in court documents that Zeng knew about this fraud, a point which the Zengs’ attorneys dispute.

Virtually none of the promised revitalization work on the mall materialized. It entered foreclosure in 2015, after which the Zengs repurchased it under their own names for $3.2 million plus debt.

While the dominoes fell on this sprawling international fraud and the mall’s title repeatedly changed hands, tenants say the shopping center languished.

“At the time they were here, it was deteriorating,” Juventino Cardona, owner of the La Perla Tapatia jewelry and watch store in the mall, said of the Zengs’ ownership. “The reason was because they just bought it for an investment. They wanted to make some quick money.”

Andy Chides, a store manager at Hector’s Cellphone Repairs & Accessories who has worked at the mall for the last nine years, said a language barrier and a general apathy by the mall manager under the Zengs turned off potential tenants.

“The previous owners, they really didn’t care about the mall,” he said. “They were just here to collect the money; that’s about it.”

Property records show the Zengs sold off the southwest corner of the mall property still held by REO Property Group for $4.75 million in 2017 and the rest of the mall for $10 million a year later.

Financial details surrounding the Zengs’ ownership and management of the mall are disputed. Attorneys for the EB-5 investors argue in court documents that the Zengs were able to illegitimately enrich themselves in the yearslong title and money shuffling surrounding the mall, writing, “This is no guilt by association. Defendants knowingly colluded in a fraud where Plaintiffs lost their investments while Defendants made millions.”

Attorneys for the Zengs dispute that characterization in court documents, arguing that the Zengs had no knowledge of their business associates’ fraudulent sources of cash.

After more than six years of litigation, the case between the Zengs and their investors was finally set to go to trial on May 2 with a verdict possible this summer. The trial was postponed at the eleventh hour pending an available court amid a COVID-driven case backlog, leaving the last threads of that chapter in the Indio mall’s history dangling in limbo.

Resurrection?

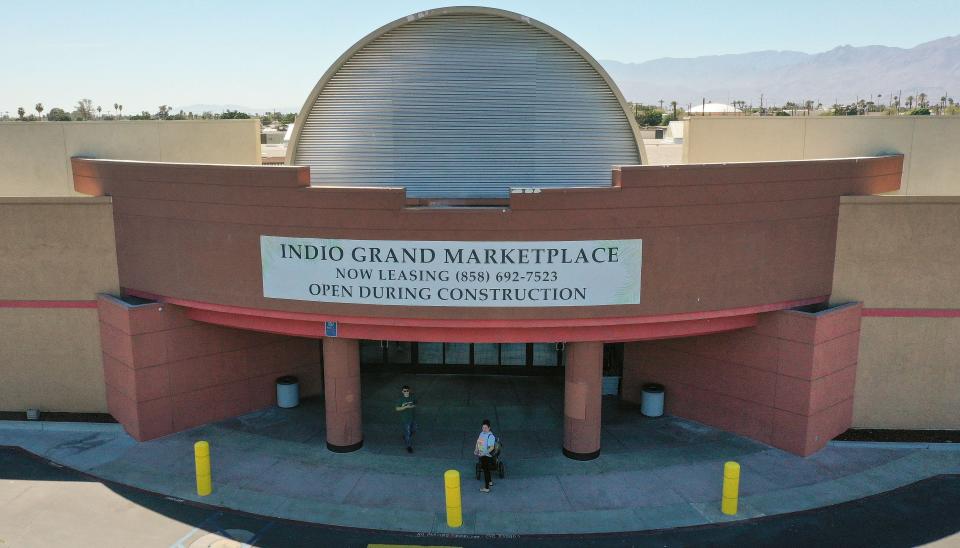

In early 2018, the Indio mall passed into the hands of its current owner, the Haagen Company, which purchased it from the Zengs for $10 million, according to property records. The roughly 215,000 square-foot mall was 70% vacant, according to a press release at the time.

Tromping fearlessly past the mall’s graveyard of failed suitors and broken dreams, CEO Alexander Haagen III picked up the gauntlet and proclaimed his intention to revive the moribund enterprise. Haagen, whose tenure as owner of Indio’s Empire Polo Club saw the site become the backdrop of some of the world’s biggest music festivals, wanted to “give back” to the city, according to Haagen Co. President Christopher Fahey.

“What really attracted us was the opportunity to turn an old eyesore around and make it an asset for the city,” Fahey said, “rather than a negative.”

Haagen Co.’s initial plans involved tearing down some or all of the mall and turning it into an outdoor retail plaza with a movie theater — an attraction often floated throughout the mall’s long history — a gym and a hotel. The plans would, yet again, incorporate the former Nobles Ranch land in a residential development connected to the mall. They renamed the mall again, this time with the ambitious title “Indio Grand Marketplace.” The company said at the time that it expected to begin redevelopment work in 2019.

That year came and went without any major changes at the mall. Haagan Co. pulled down the old “Fashion Mall” façade and hung a banner with the new name in its place.

After two relatively quiet years, the company submitted and received Indio planning commission approval for a new, less-ambitious redesign last summer.

The reworked plans, perhaps the most modest (and achievable) the mall has seen in decades, center on renovating and modernizing the existing building. They include adding a food hall, outdoor child’s play area, an outdoor “flex” area for small special events and music and redesigning the exterior of the building with a colorful, modern look. Fahey said the company plans to upgrade the interior of the mall with new colors, finishes, floor tiles and furniture. He said it also plans to replace the skylights to allow clear light to enter the mall — banishing the eternal twilight that hangs over the space.

“(We want to) make it a comfortable place for people,” Fahey said, “where people could just come sit, hang out and relax for a longer period of time.”

Specifically what stores will occupy the space is unclear for the time being. Some of the mall’s existing tenants, a mix of mom-and-pop shops such as clothing and jewelry retailers, a hair salon, a cell phone repair kiosk and an optometrist, will stay on through the construction. The theater is out, according to Fahey, who said department stores were also “not an option.”

“We’re looking at more than likely subdividing the (former) Sears and the (former) Gottschalks into smaller sizes, anywhere from 10,000 to 15,000 square feet up to 20,000 to 30,000 square feet,” he said. “We’re looking at retail operations; we’d still like to have a gym at this location as well. We’re just exploring all those options right now.”

One of the subdivided department store spaces is marked “grocery” in the city-approved designs, although Fahey said that was just one option for the space and that no grocer had expressed interest yet.

The Haagen Co. president said his company still aimed to recruit more mom-and-pop shops to join as tenants in the new mall, but noted that the disproportionate number of these businesses that closed during COVID made that proposition more difficult than it would have been in the past.

Monica Fausto, owner of the Lotus 2 hair salon, said her employees were originally resistant to the idea of moving into the mall in 2018 after a dramatic rent increase prompted her to look for a new location.

“All of them said ‘No, no, that place is no good,'” she said. The salon owner decided to chance it, however, when the new owners offered to lease her a space for about $1,150 per month — less than half of what she would have paid at her former location. She said she has been largely happy with the results.

“All of my clients follow me since I keep moving,” she said. “I’m doing pretty good.”

Fahey said he wasn’t able to provide the current occupancy rate of the mall, but that his company aimed to have the central area between the former department stores about one-third full through the renovations. A visual survey of the empty spaces in the mall suggests they are roughly on track to achieve that goal.

Fahey said his company plans to begin construction on the mall in July and estimated that it will take about one year from that point until the redevelopment is completed.

When asked about the reason for the yearslong delays to the original timeline, Fahey said the “serious” redesign work didn’t begin until 2020, after which point COVID-related delays, construction price increases and complications arising from the many “moving pieces” associated with the plan pulled the timeline back. He noted separately that the company had gone through “a whole design and development” for the outdoor mall plan before conversations with tenants and customers convinced them that the desert heat made that a losing proposition.

Fahey said Haagen Co. still intends to purchase the Nobles Ranch land and develop it into a mixed-use property with a 150-room hotel, about 300 apartment units, several restaurants and a public park. Most of the mall’s planned outdoor space — with the “flex” event space and children’s play areas — are planned for the south side of the building facing the former Nobles Ranch land.

He also said his company is currently in negotiations with the city about the purchase price and other details of that deal with a target purchase date near the end of this year. He said the development timeline for that project is more uncertain, but that he hoped to break ground on it in mid- to late 2023.

Pastor McPeters, whose church still sits on the former Nobles Ranch land, said he is ready to move on from the painful memories surrounding the location. He said he sold his land to the city in 2006 for roughly $1 million — intended to cover both the value of the land and the cost of building a new church elsewhere — and has been leasing the property back since. The pastor said he is using the sale money to build a new, modern church across town just to the north of the Heritage Palms community.

He cited issues such as the 2008 housing bubble collapse and getting water connections to the property as reasons for the 15-year delay in getting his new church built, noting separately that he wouldn’t recommend other pastors try to manage complicated building projects. McPeters said he was in discussions with the city about getting additional funding to help expedite his relocation on Haagen Co.’s timeline.

Indio City Manager Bryan Montgomery confirmed that the city was working with McPeters on “some relocation expenses” but said details had not been finalized. He said the discussions had been “very amicable” and should be wrapped up soon.

McPeters said he and city officials had been in discussions about including a tribute to the displaced residents of Nobles Ranch in the new development. Those talks, he said, had originally included preserving his old church as part of the park area, although discussions had since moved away from that idea. Fahey confirmed plans to include some kind of a tribute to the Nobles Ranch residents and history in the new development. He said his company had originally proposed a series of plaques installed throughout the park, but that the discussion is still fluid and Haagen Co. is open to other ideas.

McPeters said he felt that making something positive out of the mall and the Nobles Ranch land could be a first step in a process of healing and putting “that nightmare” behind the city.

“Whatever that is,” he said, “it’s going to start with that mall and Mr. Haagen developing that area in a way that will include a remembrance of John Nobles.”

Whether or not Haagen Co. will succeed where all others have failed and ultimately breathe life back into the ill-fated Indio mall remains an open question. Retail and real estate experts were somewhat skeptical, pointing to the widespread difficulties faced by malls similar to Indio’s nationwide.

Anthony Dukes, a USC marketing professor who studies retailing, said successful malls were increasingly falling into one of two categories: high-end “experiential” malls in high-traffic areas and outlet properties focused on attractive deals. He said malls falling in between these two categories face ongoing difficulties competing with online shopping, resulting in lower viability and higher rates of closure.

Chicago Booth’s Pagliari pointed to a March report by real estate analytics firm Green Street showing malls as one of the worst-performing commercial real estate investments in the last five years. He noted that the picture was worse for lower-end malls, and that the additional issues and costs associated with transforming these properties made any such revitalization project a “dicey proposition.”

Both professors said it was possible specific conditions on the ground could enable the Indio mall to succeed where others have failed, but suggested such success would be the exception rather than the norm for a struggling, low-tier mall.

Despite this, Indio’s Mayor Fermon expressed little doubt in the revitalization project’s outcome. He pointed to the long-running ties between Haagen Co.’s CEO and the city as evidence that the company will deliver on its promises to resurrect the Indio mall.

“He has a history and track record of going big, over-delivering and completing projects,” Fermon said of Alexander Haagen III. “He’s delivered for our community and he’s going to deliver again.”

James B. Cutchin covers business in the Coachella Valley. Reach him at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: The twisting tale of the Indio mall and what its future might hold